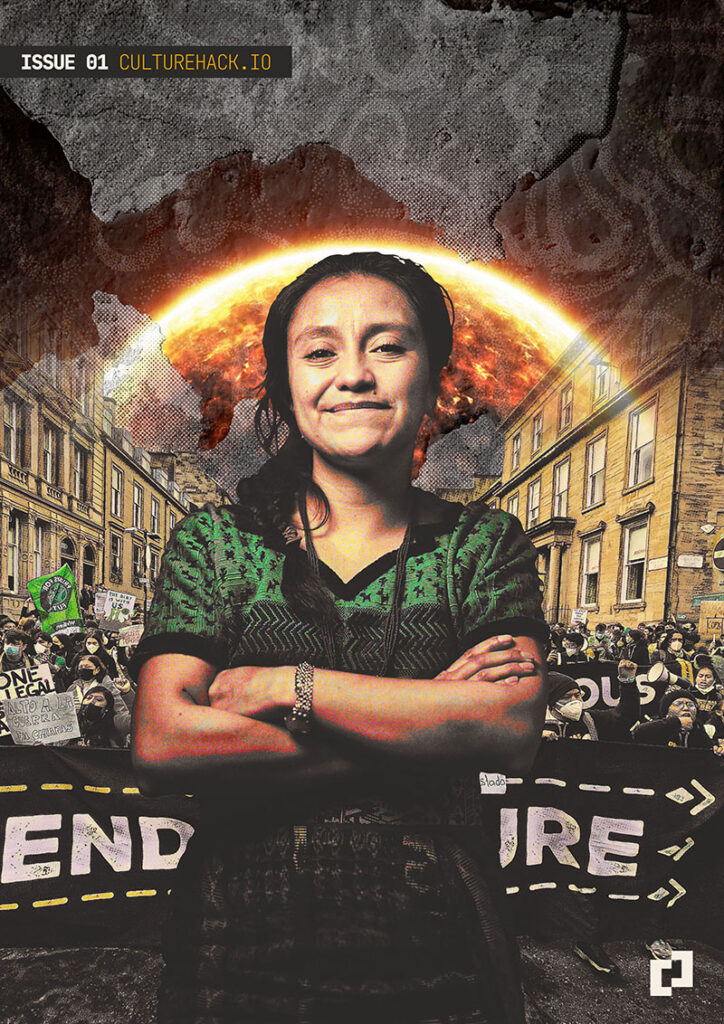

We are Nature Defending Itself

Indigenous communities like the Maya K’iche people represent the alternatives to the Anthropocene. Their knowledge and culture can allow the rest of us to imagine a new future.

Now more than ever, in this time of systemic crisis, connecting the past and the future becomes urgent. As we stand before one of the greatest challenges that we have ever faced as a species, we must now reimagine and reconstruct the ways we inhabit this planet so we can prevent rendering all life unsustainable. And while this task may seem unachievable, it really is not: all we need to do is allow ourselves to learn from the ways indigenous communities have inhabited this world.

More than five centuries of dispossession and violence have driven ancestral knowledge and many indigenous communities to a point of near annihilation. Life has been infected with a virus that places the imaginary value of money above the concrete and tangible value of mere existence.

all we need to do is allow ourselves to learn from the ways indigenous communities have inhabited this world.

The development model brought upon us by the Western civilization measures the value of our lives based on our ability to produce wealth and therefore deems the cultivation of our gifts and the transmission of ancestral knowledge in our families as archaic or obsolete. Their institutions demonize our practices, strip us from our languages, unroot us from our ways of life while at the same time they are appropriating, exoticizing and profiting from our sciences, arts and culture.

Nevertheless, throughout the centuries we have resisted by developing multiple strategies to defend our ways of life both out of self-preservation and because the effects of the extermination of cultural and biological diversity present in our territories as extreme droughts, hurricanes, famines and pandemics. As the centuries go by, our communities have continued to take the brunt of the devastation left behind by the storm of progress.

The current fever caused by global warming is a symptom of the capitalism promoted by the Nation-State that has violently and forcibly implanted an individualistic culture that normalizes the destruction of our own home and our culture in the pursuit of pointless accumulation and waste.

Talking about the Anthropocene on this day and age presents us with the possibility of thinking beyond what is human. The way academic institutions define the Anthropocene has created a wall, albeit a cracked one, aiming to shield the term from the realities of life beyond the institutions. However, it is within the cracks of that wall that the resistances and the stories that have existed for more than 500 years now flourish. In times of systemic crisis we need other paradigms to talk about its effects and aim to find possible cures, so I will now take this opportunity to talk about one of them.

In times of systemic crisis we need other paradigms to talk about its effects and aim to find possible cures.

My grandparents told me that the earth emerged from darkness and mist hundreds of thousands of years ago. From among the waters, hills and mountains were born. Creators and shapers spoke among themselves, put their thoughts together, reached agreements and then made life sprout. Tz’aqol, Bitol, Tepew Q’ukumatz, Alom, K’ajolom, great sages, came together to measure the sky, they put each star, the moon and the sun in its place. They measured the earth and settled its four corners. Then they created the animals, the guardians of the forests, the deer, the birds, the jaguars, the snakes. And after two failed attempts to form people, they managed to create the people of the corn, from whom we, the Maya K’iche people, descend thousands of years from now. Creators and shapers filled our land with pine and cypress forests and they named the land as Tayb’achaj, which later was called Chuwa’ Miq’inja and today is known as Totonicapán, located in the highlands of current day Guatemala.

Those of us who were born from one of the branches of the Maya K’iche tree learn as we grow up that our stories are as old as the forest. And like our grandfather/grandmother-forest, they are a living body.

We are the leaf and the tree, the crown and the root, plants, animals, sacred altars, water, earth, verses, spirits, loves, meanings, feelings, words, identities. When we say that we are K’iche’, we are the forest naming itself.

From a young age we learn to sow and harvest the rain. For centuries, girls, elders, men and women have protected the Communal forests of Totonicapán, we take care of them, we give them affection and the forest provides us with firewood, medicines, oxygen, and water.

We are the leaf and the tree, the crown and the root, plants, animals, sacred altars, water, earth, verses, spirits, loves, meanings, feelings, words, identities. When we say that we are K’iche’, we are the forest naming itself.

On one occasion a child from my community asked during a visit to the forest: how is water born? To which a grandfather, don Agustin Par, guardian and protector of our forest, said in response: “The earth, just like us, has veins and these are the roots of all plants. In those veins circulates the blood of the earth. “Do you know what it is?,” he asked, “Well, it is water. There, between the land and the trees, the water is stored and deposited in small springs that become rivers, lakes and seas.”

This is the reason why my people established their own forms of organization and management of nature. We have our own institutions and regulations that rule over the use of water, land, forests and all biodiversity for the benefit of all. In the K’iche standpoint of Totonicapán, water, land and forests are communal goods whose management is in the hands of the community. And when there are members of the community who violate its mandate, there are sanctions, there are consequences, there are reparations and, above all, prevention of these events ever happening again. Under this model, solving our problems is not easy, but it is possible.

I listened carefully as the grandfather tells what hydrologists describe in other ways. They speak of three great springs of water that originate in Totonicapán’s forests and that flow into the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean. It is in our ancestral forests that the Motagua, Chixoy, Cuilco, Selegua, Samalá and Nahualate rivers are born. But don Agustín describes it this way: “The water makes its way through the mountains and along the way it feeds all the plants and animals.” From the communal forest of Totonicapán, rivers are born that make their way through the mountains and cross all of Guatemala. In the more than 22 thousand hectares that compose our communal forests, water is planted for a whole country.

The K’iche vision of forests, land and water recognizes them as having their own life and personality. That is why it is important to understand how the western and capitalist logic that treats nature as a natural “resource” is a concept that guides exploitation for development and individual rights, even if it is called sustainable. This vision creates conflicts in our daily lives.

The K’iche vision of forests, land and water recognizes them as having their own life and personality.

In the K’iche language, the political and social organization model of Totonicapán is described as: “Uchuq’ab Tinamit Chuwa Miq’inja’ are ri K’axk’ol”, the Power of the People is in Community Service, this is a principle that guides us and defines community as a space where everyone participates and assumes their own responsibility. This model proposes another way of living, it is a social organization that allows us to resist the hegemonic and dominant culture imposed upon us.

From our standpoint, nature is not a resource, because it does not meet the criteria to be considered merchandise, but rather it is an element that gives us life, that sustains us. We are complementary to it, we are its tenants. For us the water, the land, the forests are sacred. “Rawasil tewechi’bal” is called, we know that protecting nature is taking care of our common home. To guarantee our life we must respect it, otherwise there will be negative consequences for everyone.

We thank the water, air, earth, and fire. We thank the heart of the universe and the earth for our lives. Our common stories root our identities in our territory and lead us to defend and protect what gives us life, especially in the face of various laws and policies that have sought to treat us as merchandise and that have tried to impose a private ownership of the land, water and forests. We organize to stop criminal groups that are seeking to prey on the forest with logging or mining.

Our common stories root our identities in our territory and lead us to defend and protect what gives us life.

Our forms of community organization have resisted despite conflicts, wars, corruption, pandemics and genocide. Ancestral lineages that protect the land and water have prevailed. We constantly fight to strengthen our system of authorities that take care of the forest, we do communal service, litigation, reforestation, communication campaigns, we do offerings and ceremonies to the water, to the land, to the sun, the rain, the wind and our ancestors.

The indigenous communities that defend their territories are living alternatives to systemic crises and their existences widen the cracks in the narrative of the Anthropocene.

200 years after the formation of the Republics, the States and their institutions have shown us their limits and all the possible faces of repression. They have shown us their active role in the destruction of the land and pollution of water and life.

The future is an exercise of radical imagination, of not forgetting our origins, of sowing today the harvest of generations to come.

Our responsibility involves strengthening the models of organization of life that build their political horizons beyond the Nation-States. It is urgent to build social practices that seek a dignified life that respects biodiversity.

What would the world be like without patriarchal, colonial and extractive systems? The future is an exercise of radical imagination, of not forgetting our origins, of sowing today the harvest of generations to come.

Every time my people mobilize to defend our territory, every time we walk through the forest to protect it from loggers, we don’t do it because we are “saving nature”, but because we are nature defending itself. The water, the land, the forest are in our blood, in our fluids, our saliva and our tears. We are part of the water cycle, river basins are the veins of the Earth and the liquid we are drinking today was rain in the forests protected by our ancestors thousands of years ago.

It is urgent that more people join and respect the indigenous resistances and share narratives and stories that put life at the center, that show us the concrete, achievable, attaining possibility of different worlds.

Related bibliography

- Maya Wuj, Ak’abal, Humberto. Paraphrase of the Popol Wuj. Guatemala 2019.

- Camey Huz, Licerio. “IT IS NOT SO EASY TO COME HERE AND FOR THEM TO COME TO SEND US…” THE DEFENSE OF FORESTS AND WATER IN TOTONICAPÁN, Guatemala 2009.

- Elías, Silvel. Komon Juyub. The territory of life of the 48 Cantons of Totonicapán in Guatemala 2021.

- Ixchiu, Andrea. Un bosque. Plaza Pública. Guatemala 2013.