Deep Dive: Understanding Narratives

Defining Narratives

As social beings, we have an immediate need to make sense of our lived experience so that we can function in our everyday lives. This ‘sense-making’ process occurs mostly in our subconscious and is brought into our conscious state by the framing of ‘raw experiences’ into understandable bits of information. This information is what we believe to be our reality, but in actuality this is only the subconscious interpretation of the sensations of our body through our own narrative frames.

At any given second, we consciously process only sixteen bits of the eleven million bits of information our senses send to our brain. This led Tor Nørretranders, the Danish science writer, to describe human consciousness as the “User Illusion”. He states:

“There are no colors, sounds, or smells out there in the world. They are things we experience. This does not mean that there is no world, for indeed there is: the world just is. It has no properties until it is experienced. At any rate, not properties like color, smell, and sound. I see a panorama, a field of visions, but it is not identical with what arrives at my senses. It is a reconstruction, a simulation, a presentation of what my senses receive. An interpretation, a hypothesis.”

The quality of our actions is then determined by the nature of the frames and internal metabolization of the information our senses send to our brain. This relationship between narratives and human action is at the heart of our inquiry in this module.

The term ‘narrative’ is notoriously ill defined yet is one that has gained increasing popularity in today’s culture. It is commonly understood as a collection of interrelated stories. This definition has some truth to it, but omits critical aspects related to the production and effects of narratives. And even more importantly, this stance remains neutral to the effects that narratives have on shaping our belief systems and thereby actions, therefore narratives carry political currency. This view of narratives is central to understanding our methodology .

The Culture Hack Methodology is based upon three key assumptions:

Assumption 1: We can gain deeper insight into human behavior by analyzing the narratives that drive them.

Assumption 2: Through the intentional and deliberate reframing of these narratives, we can bring about changes in our belief systems and actions.

Assumption 3: To dismantle systems of inequality and oppression, we need to change narratives.

Taking this into account, we can define narratives in terms of their ability to guide human actions:

Narratives are interpretive social structures that frame our experience and function to bring meaning to everyday reality, guiding our actions and decisions.

The Culture Hack methodological framework emphasizes the emergent and complex nature of narratives. In more specific terms, we are interested in determining how and why narratives come into existence and through this we can understand how they affect the world. This understanding requires a recognition of a more complex causality between narratives and humans, one that is essential for effective narrative analysis and intervention.

When we try to understand narratives from this more complex perspective, we call them narrative forms. This description of a narrative implies a morphogenetic process, which simply means that narratives emerge from causes and conditions and take differing expressions and forms. Consequently, rather than understanding narratives as a ‘collection of interrelated stories’ we propose a definition that reveals the multi-layered quality of these narratives. This is important to unpack because if we are not aware of the multiple layers that make up narrative forms, we are blind to what is driving our thoughts, beliefs and behaviors. Taking this into account, we can define narrative forms as being more than messages or stories:

Narrative forms are complex, adaptive, evolutionary systems. They are alive. They are born, can evolve, mutate, terminate and converge with other narrative forms within a specific environment or cultural context. Narrative forms drive how we collectively make sense of our reality.

It is important to understand that narrative forms always emerge within an ecosystem of other narrative forms. These narrative forms express different aspects of a social phenomena or event. For example, in the CHL Transforming the Transition Report (2020) we showed how the narrative forms of ‘solidarity’ and ‘individual freedom’ lived side by side in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. Although each of these narrative forms had very different expressions they were in an ongoing relationship with one another. Taking this into account, we can define this as the narrative space:

Narrative spaces are models of the relationships between narrative forms within a time frame. Through this model we can understand their interactions and dynamics.

Principles of Narrative Forms

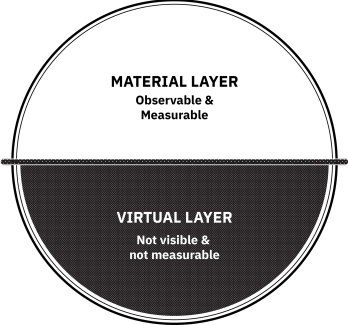

As illustrated by Figure 1 below, narrative forms can be described using the following four principles (which is essentially a summary of what you have learnt so far about narrative forms):

1. Narrative Forms have a material layer that is clearly visible and measurable.

2. The Narrative Form has virtual layers that are not visible or measurable but deeply influences the material layer.

3. Narrative Forms are produced through cycles that move between the material and virtual layers.

4. Narrative Forms are emergent, complex and in flux. They interact and can influence each other.

Figure 1: Principles of Narrative Forms

Let’s take a deeper look at each of these principles to get a better understanding.

Principle 1: Narrative Forms have a material layer that is clearly visible and measurable.

We can find evidence of narratives through their material expressions and communications, which include speech acts, images, text, video, clothing and or other cultural artifacts that we encounter in our daily lives. Most often, as narrative analysts, we look for evidence in the media; for example, in news articles, opinion pieces and social media posts. However we can also collect this data through interviews, surveys or other traditional ethnographic methods. This dimension takes the shape of those material expressions and communications.

As we will see in Module 5 Listening to the Narrative Space there are structured ways in which we can collect this data and make sense of it, aligned with our overarching strategic goals.

Principle 2: The Narrative Form has virtual layers that are not visible or measurable but influence the material layer.

This second principle holds that while narrative forms have a material layer that is clearly visible and measurable, they also have a virtual layer that is not visible but can be inferred. It is important to understand that the material and virtual layers of a narrative form are different from each other but are dependent and exist in tandem with each other. Take a fictional story for example; the physical book itself is the material layer of the narrative form whereas, the story itself, is the virtual layer of the narrative form.

A novel is a simple example, but very often narrative forms are far more complex. In most cases there are hundreds, thousands and often, millions of material expressions of a narrative form. The core idea is that all material expressions of a narrative form are the result of a virtual cultural process. Moreover, it is not always easy to decipher how the material and virtual layers are connected. However if we have a basic model of how narrative forms exist we can make this analytical process easier. You will learn more about this in the next unit.

Principle 3: Narrative Forms have genealogies, produced through cycles that move between the material and virtual layers.

The third principle describes the way the material and virtual layers of narrative forms (principles 1 and 2 respectively) are interconnected, interdependent and mutually support each other. These layers exist at the same time and inform each other; the material layer is produced by the virtual layer and the virtual layer is produced by the material layer. This third principle is critical in understanding how narratives work but also how we can work to change them, and therefore make the impact in the world that we seek.

Let’s take music as an example. If we look at any one music genre, we will see a rich landscape composed of multiple expressions as sounds, instruments and voices (material layer). Then, if we compare several generations of the genre, we will notice two things – firstly we will observe recurring patterns (virtual layer), and secondly we will observe novelty, improvisation and change in the form of new patterns (the effect of the virtual layer in time). For instance, in the Hip Hop genre, we can observe basic genetic patterns in the music that connects it to its antecedents such as to Jazz, Gospel and The Blues. However there are also expressions that are idiosyncratic to Hip Hop, and in fact, it is these which allows us to identify it as an evolved form. Similarly, this principle holds true for many cultural phenomena such as cinema, religious beliefs, political theories and almost every aspect of our social lives. In sum, narrative forms have a genealogy that we can analyze to understand them better. To see this illustrated see Music Map for a relational map of music genres in the western world.

Principle 4: Narrative Forms are emergent, complex and in flux. They interact and can influence each other.

That narratives are emergent and interdependent social processes, is the fourth and final principle of narrative forms. Narratives are social assemblages, emerging in dependence of causes and conditions within coordinated social networks. Social assemblage , is a term that was developed by complexity theorists to better understand cultural systems by positing that social phenomena cannot be reduced to a set of atomic units, but rather that they are emergent, complex and in flux. Understanding narratives as interdependent social processes or phenomena and the implications of this emergent complexity on our work as narrative change agents is crucial.

Through this, we can start to understand narrative forms as cultural processes that cannot be reduced to any single set factors. As we try to find an originating point or essence of a narrative form, we find instead a series of further causes and conditions or dependencies. We see evidence of this in the semiotic structure of plots in stories and in movies.

In this scene from The Matrix for example, we have a richly layered set of references from Lewis Carol’s Alice in Wonderland to Baudrillard’s Simulation and Simulacra; that function to create a meaning framework for the narrative architecture. Furthermore the assemblage of narrative elements have an aesthetic quality that engenders a particular sense within the viewer. As Lakoff & Johnson indicate, narratives are active at the subconscious and embodied level, or the sense (aesthetic) level we may say. This means that although we are not always aware of the multiple layers of a narrative form, they function to bring our awareness into a specific cultural disposition.

Layers of the Narrative Form

Now that we have a working definition of narratives and an overview of the principles of narrative forms, what follows is a model that will help you analyze the layers of narrative form.

The Material Layer of the narrative form consists of actions and expressions within the narrative space. This material layer has two sources – the first is from the narrative form itself and the second from other narrative forms within the narrative space. The Cura de Terra case study is a good example of this. The local political event of the deforestation of the Xingu Basin in the Amazon Rainforest required an understanding of adjacent narrative forms within the local region, and their relationships within the narrative space. Additionally, it was also critical that we understood the global narrative patterns that affected the narrative space. We saw this in our work with local Indigenous movements in the Xingu Basin during the onset of the Covid Pandemic in 2020. In this case, we saw an intersection of narrative forms – protecting the land and protecting the body during the COVID19 pandemic. The result of this intervention was the “Cura da Terra ” campaign that proposed the frame “We are the cure” as a narrative re-frame. For a deeper dive, you can see the Cura da Terra website.

The virtual layer of the narrative form is a transcription of everything that is happening in the material layer of the narrative form into sensations, concepts and intentions. It is useful here to think about how cognition works in our bodies. When we are walking, our bodies are sensing the environment, this information is made into concepts about the road and thereafter we can develop intentions about our next steps. This understanding of cognition (named below as sensation, concepts, intentions) is called the Embodiment Cognition Thesis and has gained much traction in cognitive science in the last two decades. For an overview of this subject please see A Brief Guide to Embodied Cognition by Scientific American; and for a deeper dive refer to the Embodied Cognition chapter of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

In our narrative form model, this is called sensation, conception and intention:

Sensation: This first process uses all 5 senses to transcribe non-representational data (such as light, heat, sound etc.) in the environment into understandable bits of information, or symbols (perceptions).

Conception: In this second process, these perceptions are placed within a structure of meaning, in the form of concepts.

Intention: Finally as these concepts are placed in broader structures of meaning that relate to self and social awareness, intentions emerge guiding decisions and actions.

Narrative forms function in the same way as our bodies, except that sensation happens not just through one human body but through multiple human bodies in coordinated and connected networks (social networks). We will delve deeper into these social networks when learning how to map narrative forms. The key idea is that narrative forms are dependent on the embodied cognition of individuals. It is difficult to know the exact processes that occur from sensation, conception and intention in narrative forms. The narrative model that we propose has been borne out of our research and is our current operating conceptual model.

Narratives allow for collective sense making. To provide a further description of the deep level of the virtual layer, we can divide this collective sense making into three processes.

The first process is creating concepts from perceiving bodily sensations through frames and metaphors.

Frames are largely subconscious, narrative structures which allow us to immediately make sense of the world. These frames are more than linguistic, and operate at the embodied and subconscious levels of cognition . We place a specific emphasis on frames in our work. This is because frames integrate all the other levels of the narrative form into one coherent ‘view’. For example, the frame of ‘economic growth is life’ utilizes the primary metaphor of ‘life is growth’, the ideological construct of neoliberalism and its correlated logics of competition, and self determinism into a coherent worldview. Therefore by clearly defining and understanding dominant frames within a narrative form, we can understand the larger semantic structure of the narrative form.

Metaphors not only structure the way we communicate but also form the basis of the frames we use to make sense of the world. In particular primary metaphors are fundamental cognitive structures that we often do not question. For example the primary metaphor that “growth is good” is an essential part of our understanding of the capitalist world and how to operate in it. It is hard to overstate the importance of a metaphor in the transcription of sensation to concepts, and it is for this reason that we must strive to surface and understand the metaphors that we live by.

The second process moves from concepts to intentions through ideological constructs and logics.

Ideological Constructs bring multiple frames into larger structured relationships. These frames are coordinated through a system of justification. For example the ideological constructs of neoliberalism give meaning and justification to the frames of ‘economic growth’.

When we go deep into these systems of justification we can see Logics. For example, the logic underlying the ideological construct of neoliberalism is that you need money to live, therefore money = life = god.

Truth Constructs then are the representations of the core beliefs that bind the narrative form together. An example of this would be that as individuals we are self interested rational actors. This is a foundation of neoliberal economic theory. It is important to remember that in reality the narrative form cannot be neatly parsed out into discrete units as we have done here, but in fact these parts are deeply interwoven and entangled. However these units are very useful for analytical purposes, and specifically so that we can create maps of narrative forms for our work.

Footnotes

- Nørretranders, T. (1991). The user illusion: Cutting consciousness down to size. Viking.

- See practitioner overviews on narrative change that explicitly connect narrative, beliefs and political action: Narrative Initiative (2017). Toward New Gravity: Charting a Course for the Narrative Initiative; Frameworks Institute, (2020). Mindset Shifts: What Are They? Why Do They Matter? How Do They Happen?; Ganz, M. L. (2001). The power of story in social movements (on the power of narrative to mobilize people); Robinson, R. (2018). Changing our narrative about narrative; See how pop culture is used as a vehicle for narrative change (or “cultural strategy”): Chang, J., Manne, L., and Potts, E., (2018). A Conversation about Cultural Strategy. Medium; Potts, E, Lowell, D and Manne, L. (2022). Spotlight on Impact Storytelling: Mapping and recommendations for the narrative and cultural strategies ecosystem. Liz Manne Strategy; Changing narratives is activism at the point of assumption (intervening at the level of belief systems): read more on Beautiful Rising about activist points of intervention. This narrative change activism (at the point of assumption) is based on research from Neuroscience, Cognitive Linguistics and Psychology: Kahneman, D (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow; Lakoff, G. (2014). The all new don’t think of an elephant!: Know your values and frame the debate. Chelsea Green Publishing; Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Vintage.

- Deleuze, Gilles; Guattari, Félix (1993). A Thousand Plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; DeLanda, Manuel (2006). A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. Read overviews through the Wikipedia “Assemblage” page or Little, D. (2012). Assemblage theory. Understanding Society Blog; Read more about Deleuze: Smith, D., and Protevi, J., (2020). Gilles Deleuze. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy or listen to podcast: The Perspective Project Podcast. (2019). Ian Buchanan on Assemblage Theory (Deleuze), Control, Society and More.

- Lakoff, G; Johnson, M (1999). Philosophy In The Flesh: the Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought. Basic Books.

- Varela, F., Thompson, E. and E. Rosch, 1991, The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Read more from Cognitive Linguist George Lakoff (the “father of framing”): Lakoff, G. (2010). Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environmental communication, 4(1), 70-81; Lakoff, G. (2002) Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Browse videos/lectures on Lakoff’s website. Chong, D., and Druckman, J. (2007). “Framing Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 10: 103–126; Benford, R. D., and Snow, D. A. (2000). “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–639.

- Read more about the logics and ideological content of neoliberalism: Monbiot, G. (2016). Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems. The Guardian; Vallier, K. (2021). Neoliberalism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Or read short overviews for activists through Beautiful Trouble or Global Social Theory.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1981). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press. (Watch a 12 minute video summary of the book; find out more through: a 5 minute video, 20 minute podcast). For more practical guidance on use of metaphor in narrative change activism, see: Frameworks Institute (2020). Tapping into the power of metaphors.

- See overviews: Freeden, Michael. Ideology: A very short introduction. Vol. 95. Oxford University Press, 2003. Especially: Chapters 1 (Introduction), 10 (Conclusion) and 7 (micro-ideologies); Maynard, J L. A map of the field of ideological analysis.” Journal of Political Ideologies 18, no. 3 (2013): 299-327; Freeden, M. and M. Stears (eds), (2013) The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies. Browse different ideologies and their logics (from Communism to Anarchism to Green to Feminism). Read about the concept of ideology in the more critical Marxist tradition (Frankfurt School, Gramsci, Laclau and Mouffe, etc.): Mouffe, C. (1979). “Hegemony and Ideology in Gramsci.” In Gramsci and Marxist Theory. London: Routledge; Or a summary of Gramsci’s concept of hegemony. Read about how practitioners have talked about the importance of ideology: Hinson, S (2016) Worldview and the contest of ideas. Grassroots Policy Project; Kirk, M., Hickel, J., and Brewer, J., (2017). “All Change or No Change? Culture, Power and Activism in an Unquiet World.” State of Power.

- For further examples of logics – see this Deleuze-influenced Philosopher’s discussion on the culture of crisis during the War on Terror and “preemption” as the operative logic of our time: Massumi, B. (2015). Ontopower: War, powers, and the state of perception. Duke University Press. 11. Goswick, D. (2020). Constructivism in metaphysics. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Critical Constructivism (Global Social Theory)

- Goswick, D. (2020). Constructivism in metaphysics. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Critical Constructivism (Global Social Theory)