Amazon Avengers: Meet the Next Generation of Indigenous Earth Defenders

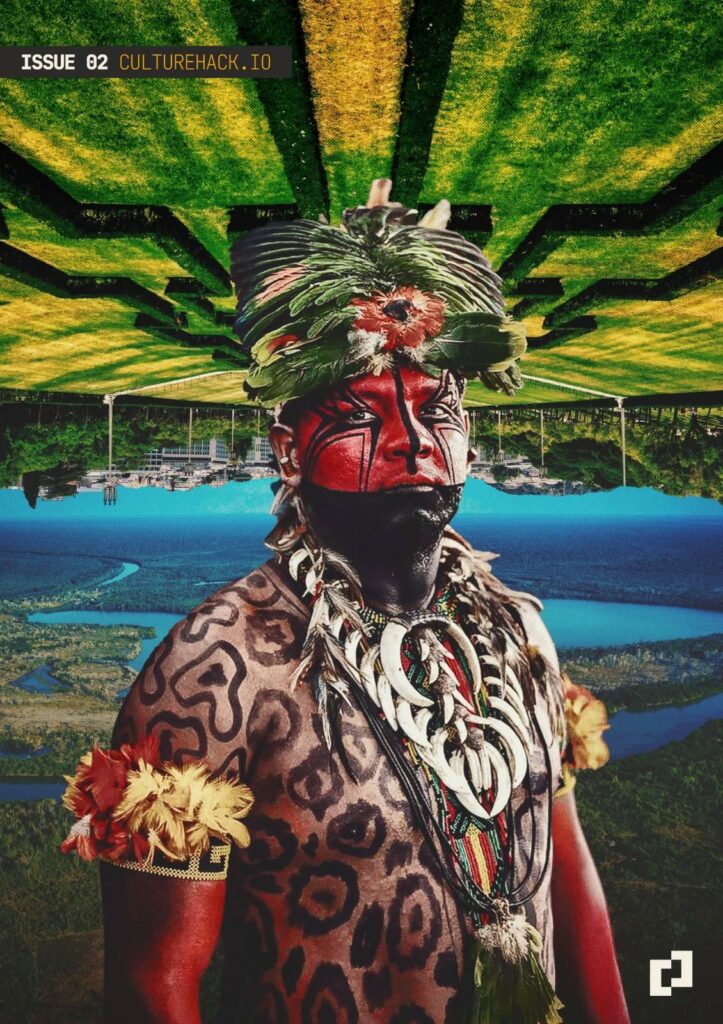

Indigenous peoples in the Amazon have long risked their lives to defend the rainforests that are their home. But a new generation of activists is widening the fight, seeking to seize control of a much larger territory – challenging our entire economic system and very way of life.

“And nobody was angry enough to speak out” — ancient graffiti, found on the Pyramids in Egypt (UNCOP27 host)

There can be few starker illustrations of the deluded logic of extractive capitalism than the spectacle now unfolding in the Amazon. Even with awareness of how critical the protection of our rainforests is at its zenith and following the publication of a quick succession of ever-more alarming reports on Earth’s capacity to sustain life, the Amazon this year has been burned and felled at an extraordinary speed and scale, with 1,540 square miles destroyed between January and June alone, an increase of 10% on last year. June has seen the most fires in 15 years.

We are witnessing the concerted annihilation of vast tracts of one of Earth’s oldest, most vibrant living ecosystems and one of its most critical life supports. This annihilation is taking place to make way for the growth of Brazil’s cattle-farming, soya-growing and mining industries. This is to risk Earth’s very habitability for economic growth. These are acts of self-destructive vandalism that will impact every person on Earth, funded by investment firms in London and New York: chiefly Black Rock, Vanguard and State Street. The impunity and sheer stupidity of these investment decisions will surely stun future students of history: vast as the Visigoths’ sacking of Rome, sacrilegious as the Talibs’ bombing of Bamiyan.

For the Indigenous peoples that call these forests home it all amounts to devastation of an enormity that is hard to fathom unless you’ve travelled to these lands, and walked in their footsteps. But we would all do well to attempt to imagine the immensity of their losses. For with the falling of each tree, they lose so much more than what registers on global balance sheets as some far-off, vast carbon sink. These forests are beloved ancestral lands, lifelines, medicines, livelihoods, places of worship and provide access to the natural wonders that these groups have guarded with vigour, reverence and wisdom for literally millennia. These tribes have watched, year by year, as these natural birthrights are razed to the ground.

Devastation for the trees that breathe the world: places that once teemed with bark, leaf, web, sapling, rendered inert, barren as moonscapes as, over the course of the last 50 years, nearly a fifth of the Brazilian Amazon’s forest cover has been lost.

It results in devastation, too, of course, for the more-than-human world: all those species of birds, mammals, insects and flora that each arose and can only thrive within the web of complex interdependence found here. Devastation for rivers that now flow so poisoned that no fish can live. Devastation for the trees that breathe the world: places that once teemed with bark, leaf, web, sapling, rendered inert, barren as moonscapes as, over the course of the last 50 years, nearly a fifth of the Brazilian Amazon’s forest cover has been lost. 275,000 square miles.

Here, far from the eyes of the world’s media, and the well-heeled, sanitized money markets that are its metropolitan veneer, extractive capitalism forces its way through these pristine forests like a Death Machine. There are the quick murders: of thousands of trees of course, and the sudden disruption to or deaths of lifeforms, from beatle and bug to jaguar, that each of them will have sustained until their fall.

And there are the quick, violent and unjust deaths meted out to the humans that seek to defend these forests. The murder of Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Philips this year were uniquely high-profile but they were, far from being isolated incidents, instead a chillingly familiar way of silencing or intimidating those who choose to fight deforestation in the world’s rainforests. Worldwide, four land defenders have been killed each week since the Paris Climate agreement was signed. Most for opposing deforestation, and far too many of them, in the Peruvian and Brazilian Amazon.

There are more distant casualties as well. To see and feel these deaths requires we widen our lens, to squint beyond Brazil’s borders, to follow the laws of physics as well as those of forest ecosystem and finance, and to see the link between rainforests, the wider climate and rainfall. Because deforestation is second only to the burning of fossil fuels as a source of greenhouse gas emissions and since the capacity of the world’s three major rainforest zones, the Amazon, the Congo Basin and the forests of South-East Asia to conserve, cycle and harvest water impacts water cycles worldwide, deforestation in these regions is contributing to the bizarre cycles of boom and bust in rainfall that we are already witnessing the world over, from Surrey to Switzerland to Sichuan. These cycles are major drivers of the droughts and floods that are transforming productive arable land into deserts and ushering in famine situations and refugee emergencies everywhere from the Horn of Africa to swathes of Asia and the Middle East.

So many deaths already from the Amazon’s deforestation, both within Brazil and beyond its borders. Small wonder that Jonathan Watts, the Guardian’s Global Environment Editor, in his eulogy for his colleague Philips, carefully chose to call him a war, not an environment, correspondent.

And there are innumerable deaths to come, of course: of those that have not even been born or dreamt of yet. As Chico Mendes, the unionist and environmentalist who helped establish legal protections for the Amazon’s tribes and rubber tappers, said, before his own murder, in 1988: “At first I thought I was fighting to save rubber trees, then I thought I was fighting to save the Amazon rainforest. Now I realize I am fighting for humanity.”

John Donne once wrote that, “Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind. And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.” It could not be more apposite to this moment. Each of these deaths does indeed diminish all of us. As we stand at code red for humanity, each bell tolls for us all. And if we listen, it also calls out to every one of us to rise up and reject the structures and systems that enable the pursuit of private profit and economic growth at the expense of life.

Despite its veneer of propriety, given its death toll on biodiversity, land defenders and trees in the Amazon and in its wider impact on the very habitability of Earth’s systems, the hands of extractive capitalism are soaked in blood.

Because despite its veneer of propriety, given its death toll on biodiversity, land defenders and trees in the Amazon and in its wider impact on the very habitability of Earth’s systems, the hands of extractive capitalism are soaked in blood. With the world’s three largest investment companies continuing to invest more than £8.6 billions in companies linked to the Amazon’s deforestation there’s no sign of that bloodshed abating.

But through the veins of those coming of age right now in the Amazon, who have witnessed this with most clarity for the longest, pulses the blood of vengeance. Against all the odds and after 500 years of oppression, pillage and genocide, a new breed of resistance fighter is rising up. These new Indigenous leaders, in Brazil’s many biomes and beyond, have a clear vision of the urgent need to overthrow an economic system that is killing us—quickly and closeby; indirectly through changing weather and water patterns and in distant places; in the past; or in the future: whose lives we might yet save if we avert the worst.

These activists, more than merely resisting capitalism’s encroachment on their lands, are themselves the living embodiments of the sorts of generous, alternative, gentler modus vivendi that, if more widely embraced by societies in the Global North, could hold the key to both planetary and species survival. And they are stepping out from the shadows of centuries of disenfranchisement and speaking out and calling for action with a ferocity, creativity and clarity that calls for all of us to respond.

25-year-old Indigenous activist Txai Surui, is typical of this articulate, charismatic new breed of leader growing too prominent to ignore. Txai shot to the spotlight with a striking speech at the start of the UNCOP26 in Glasgow, asking: “Will the countries that promised to uphold human rights and protect the Earth keep their word? How many more will be killed in a senseless war on the environment and those who protect it before things change?” Txai tells the story of her people, the Ure-re-wau-wau, in an award-winning documentary, ‘The Territory, recently acquired by National Geographic. It centres on Rondonia, one of the portions of the rainforest whose decimation by land-clearance satellite imagery from 1975 harrowingly revealed.

Celia Xacariaba is another luminary of the new wave. In a stunning reversal of traditional power imbalances, she has just been elected as the first indigenous federal lawmaker in the Brazilian government – representing Minas Gerais. Two years ago she was among a group of indigenous women from communities across Brazil who came together to launch ‘Cura da Terra’, an initiative designed to catapult Indigenous leaders onto the world stage so that their voices can be heard. Cura da Terra (Cure of the Earth in English) aims to co-create narratives of responsibility, reciprocity and regeneration. In Celia’s words, “In the midst of this extermination, we, Indigenous women, make melody of the struggle, while we recover land stolen from us, we insist on celebrating our existence. We sow hope. We, ourselves, are the very Earth healing itself.” Celia is actively setting out, in the teeth of our collective crisis, to nurture resilience—inspiring people in Brazil, and the world over, to embody a new old way of living in connection with the living world to which we all belong.

Both Eric Terena’s parents were pioneering activists who helped launch the indigenous rights movement in Brazil. Now Eric, journalist, DJ, multimedia artist and organiser, is picking up the baton, but using new techniques: founding indigenous storytelling network Midia India and foregrounding the use of story and music to communicate social and environmental struggle. “Since colonization began in Brazil, Indigenous peoples have been silenced,” he says. “Therefore, we have had to constantly speak up and make our voice heard—to share our stories, to highlight our lives and our struggles. Photography and film have both been fantastic tools to raise awareness amongst non-Indigenous peoples, and educate white people about our culture so we can work together to preserve our territories and sacred biomes. “Art has the power to communicate directly to the heart and bridge different worldviews,” he explains.

It has been said that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than an end to capitalism. But as Ursula Le Guin said, “Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.” Emergent leaders like Celia, Eric and Txai not only have the spirit, courage and independence of thought to imagine the end of extractive capitalism, they are already its living embodiments. They have rejected the idea that the end of the world is inevitable, fixing their sights firmly on imagining capitalism’s demise instead. In its place, they propose a possible new path, a new story that can propel us forward. As they say: ‘O futuro e Ancestral’ (the future is indigenous).

Perhaps one of the greatest acts every one of us can make right now is that of actively hoping and collectively imagining alongside Celia, Eric and Txai—noticing their words and stories and with them imagining a world of flourishing so powerful that there leaves no tolerance for a story of inevitable extraction and destruction. Julian Brave Noisecat, the Canim Lake Band Tsq’escenthe writer once advised “the so-called civilized world [to] become just a little bit more Indigenous, rather than the other way around”. If we did, could we be poised on the cusp of a systemic shift? Might it just be possible to usher in a change of epoch-shaping proportions? What is next and which turn the world takes is up to all of us. But as Eric says, “Racialized capitalism doesn’t only affect indigenous peoples but all of us. We desperately need to find a new way forward.”

Footnotes

- Deforestation is second only to the burning of fossil fuels as a source of greenhouse gas emissions, which scientists link to climate change. Researchers say halting and reversing land clearance in tropical forests could reduce global carbon emissions by nearly a third.

- Brazil exports 20% of the world’s beef, and is the world’s top producer of soy. With prices for gold and other metals on the rise, illegal mining footprint on Indigenous land within Brazil has risen by 500% in the last decade alone.